Tang Family

Tangs and Surgeons — Family Acanthuridae (thorn-tail)

Tangs fall into the family Acanthuridae, a name which means thorn tail, and is translated into their nickname “surgeonfishes”. This name stems from the spine found on either side of their tail, which are surgically sharp and to be avoided. In larger tangs, these spines can cause deep cuts as if with a scalpel.

Some tangs species remain fairly small (several inches to around a foot) but the largest can reach three feet and are a featured food fish in the tropical areas where they are found.

Tangs have a small mouth which is pointed and extended and has a single row of teeth. Many feel they are vegetarians, but we observe they are quite the omnivores, eagerly accepting most seafoods, though most do need algae in their diet to keep the cultures in the GI tract healthy and functioning.

The most popular tang has been the yellow tang, found in Hawaii and some archipelagos west of Hawaii. This fish was immortalized in the Disney movie “Finding Nemo” as “Bubbles”. The largest population of yellow tangs is found in the southeast of the Hawaiian chain on the big island, particularly on the western coast of the big island, the Kona area. We have observed that the densities of the population increase as you travel from the Northwest islands of Hawaii towards the Southeast islands, till you come to the last one, and there one finds the largest populations on the western shores of this most southeasterly island at Kona.

Since the larva of the yellow tang is capable of remaining as a plankton in the water column even after the larval period, we have speculated that perhaps since the prevailing currents are following the chain from the north west to the south east, it is possible that the brood stock for each island is towards the northwest and the broodstock on the big island may very well be losing their spawn to the pelagic spaces. If this is true, the most sustainable practice would be to protect the populations in the northwest islands as broodstock and only collect on the big island, near Kona.

Hawaii boasts several species popular and important to the aquarium trade, starting with the yellow of course, but also including such popular animals as the Kole Tang, the Achilles Tang, and the Chevron tang. These three are found in far fewer numbers than the yellow tang. In fact, the name Gold Coast of Kona was inspired not by gold in the hills but by the yellow color often seen in the waters off Kona due to the very large populations of yellow tangs.

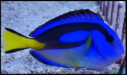

Throughout the Indo-Pacific from the Vanuatu and the Solomon Islands in the east through to Papua New Guinea to the west and the Philippines to the north are found a wide variety of attractive tangs, not the least of which is the blue tang, made famous by the Disney movie “Finding Nemo” in the character “Dori”. The Indo-Pacific region is home to many popular genre of tangs, including the nasos, bristletooths, and Zebrasoma, among others.

A very popular tang is the purple tang, found in the Red Sea and generally very expensive in the hobby. It can be somewhat unavailable to the trade due to the political and geopolitical instabilities surrounding the Red Sea area. Years ago the Saudi’s allowed collection and importation but no longer allow this. The Gulf of Aqaba near to Jordan is a very large long protected marine sanctuary and therefore makes collecting there a logistic challenge, and it is a long drive to Jordan’s capital Amman from Aqaba where there are direct flights to the US. Of course political troubles in places like Yemen, Sudan, Egypt and Somalia make collecting in Red Sea very challenging at this time.

Conditioning tangs for spawning is a fairly straightforward task given the right Broodstock, conditioning, and holding facility, however raising the larvae through the first few weeks, one faces a large challenge similar many marine species of interest to the hobby: finding a suitable live food for early feedings.

The larvae are smaller than the larvae of other successfully raised aquarium fish, and it is thought they prefer to eat small copepods that do not easily lend themselves to the dense cultures required for breeding operations. These copepods have a jerky motion that attracts these larvae and elicits a feeding response, whereas even a small rotifer swims smoothly and escapes the larval fish’s attention and reaction. So this is a very worthy problem to crack!

In the mid-1800’s, these larval tangs were incorrectly identified as their own family (Acronuridae). Later it was discovered that these fish (now termed the “acronurus” stage larvae) grew and developed into tangs!

SA through its SI unit seeks to procure small juvenile tangs at the settlement stage, ideally the late acronurus stage, leaving the broodstock in the ocean to continue reproducing. These fish are then acclimated, socialized, and raised in aquarium conditions in the SI facilities, learning to eat easily-obtained diets and feeds so to assure high survival rates in retail and hobbyists care.

Tangs can live for a very long time. For instance we have in our hatchery tangs that we have kept for more than 13 years and are very healthy and energetic, so these we believe are about 15 years old or more. Yellow tangs in public aquariums have been documented as living for more than 40 years! We don’t know how long they live in the wild, since predation is a key morbidity factor. We do know that moray eels depend upon tangs as an important source of food, and given that the tangs are diurnal and the eel nocturnal, as the tang finds a sleeping perch tucked into a rock space, the eels begin their nightly hunt.

Keeping tangs in an aquarium presents limited challenges which need to be respected:

- Tangs can have a big appetite and grow quickly! Their swimming and feeding habits dictate that they are provided with a spacious and well-filtered aquarium. Given these conditions, many species can be long-lived and personable pets.

- If one wants to put more than one of a species in a tank, it either needs to be very large or one needs to think about combining a larger quantity, more than half a dozen or so to create a group and spread-out and minimize aggression;

- They do need a portion of their diet to include vegetation. We often provide “Nori” seaweed which can be purchased unseasoned from grocery shops, as an excellent source of this vegetable portion of the diet. It can be secured with a clip or a rubber band to a rock or a piece of PVC. The tangs at SI are accustomed to grazing on both Nori and live algae clipped underwater.

- We also feed our tangs the SA Hatchery Diet, which includes a full cross-section of dietary needs, including marine-sourced plant materials. We understand that in the ocean, tangs are eating small animals continuously along with their grazing and benefit from a large portion of their diet including protein and the essential fatty acids and antioxidants found in the SA Hatchery diet. It is worth noting that most all prepared fish foods we have examined are completely composed of proteins and fatty acids which have been “cooked” at temperatures far exceeding the denaturing point for the essential fatty acids and antioxidants they contain. The SA Hatchery Diet is the only prepared food of which we are aware that assures that there is a proper ratio of protein and fatty acids and antioxidants undamaged by such cooking.

- It is interesting to note how early many of these animals were identified, a large number in the 18th and 19th century time frame. Many tangs have been used as food and as bait and many are easily caught in nets when they are larger.

- Tangs spawn in the wild generally following a lunar cycle, at or after dusk, working in a circle in the water column from the bottom to the surface of the water. Some spawn in groups, others such as the yellow tang in groups or pairs. The fertilized eggs are slightly buoyant. Most all tangs are clearly males or females, not hermaphrodites.

- Males search-out gravid females, and they rise as a pair toward the surface, often several times. They release the gametes as they come to the top of their rising spiral. Females are generally thought to spawn once a lunar cycle but males may mate many times a month.

- Generally the eggs hatch in a matter of a couple or few days and the larvae survive on the egg yolk for a couple days and on around day four begin to feed on plankton.

- They exist in the pelagic spaces eating a variety of planktonic foods for about 40 days, at which time is it believed they are capable of settling on the reef. When they pass over a suitable location, they come in over the reef crest and settle on the reef.